Over the past few years “influencer” has become a word on everyone’s lips: Advertisers choose to throw large budgets at “influencers” to shill their products and while the impact of these “influencers” is questionable at best, the perception of their lives as people who travel the world, all-expenses-paid, getting free stuff delivered to their homes AND getting paid for scrolling through social media all day long has become an even greater American Dream than Hollywood. It appears as if EVERYONE wants to be an influencer nowadays. People adopt the narrative of speaking to a mass audience.

As someone who’s been in the media industry for over two decades, I have supported many organizations – companies, non-profits, celebrities, and artists – in their goals of developing communities and building their digital presence. I have watched as the purpose and the business of social media has grown (some might say “metastasized”) and changed. I worked with talent facing the media and with the media chasing the talent. And I’ve been a talent myself. I have adapted through every development from traditional media to today’s social media. This article is about what I’ve learned about the “influencer industry” in the past few years, both from the perspective of advertisers and of the “influencers” themselves. Some of these revelations were shocking to me. Some of them just made my therapist rich.

It was only after my podcast, “Daddy Squared” became popular and my Instagram following increased dramatically, that I was suddenly seen as “one of them” and started to receive nearly daily requests for “collabs.” While it felt good, almost addictive, to receive a steady stream of love in the form of “likes” for every post I uploaded, I caught myself counting, comparing, judging, and identifying ‘competitors.’ The dependence of my income on Instagram numbers decreased my mental health, and while I never actually talked about it with my fellow ‘gay dad influencers,’ some of them suggested to me that they feel the same. For a moment I forgot that I am a podcast host and therapy activist because the followers voted “thumbs up” on what I had to say only when I took my shirt off.

“Influencer”: What Does it Even Mean?

It was Instagram that brought the term “influencer” to the fore. The concept suggested that if thousands of people choose to follow you, even if you don’t have any particular talent, you can use your popularity to sell them stuff. With Instagram being a photo-based app (at the beginning), the main question ‘why would I follow this person’ was usually answered by ‘because they are hot.’ Consequently, other than major celebrities, the hot and sexy people were those whose number of followers increased dramatically in the early days of the platform. Soon enough, Instagram had turned into a popularity contest high school-style, but with a validation number (which we all know can be crushing for mental health). It was all about how many followers you have.

At that point, advertisers assumed that the followers would buy whatever the popular kids are offering because everyone wants to be popular. If people like to look at beautiful people, they might as well watch beautiful people hold their products. This concept, in and of itself, makes sense since advertisers have paid for models to present their products for ages. The problem was that “influencers” were suddenly trusted to be all things: model, salesperson, marketing creative – all this with the theory that because I use this product or service and you follow my every move for no particular reason other than how hot I am – you will buy it too. In theory it sounds amazing – but is this actually what happens?

A Little History

Influencers were here long before Instagram. Paris Hilton was the first one who actually became famous for being famous. The gossip columns were obsessed with her, she had fortune and fame, and many girls found her life desirable. It wasn’t long before advertisers discovered the potential of her growing following and Paris’ business became being seen “wearing this” or “going there” – which resulted in her girl following seeking to do the same. It was a win-win business: gossip columns had more Paris stories that sold papers; advertisers converted their investment in her into $$$ and wanted more, and Paris could just settle in being Paris and not bother doing anything, standing for anything, developing an actual talent. And then EVERYONE wanted to do just that.

Out of the millions of Paris-wannabes only ONE person actually managed to become it: Kim Kardashian. Kim picked up the torch (some might say doused it in gasoline) of being famous because you’re famous, but what separates her from all the other millions of Paris’ fans was that, like Paris, she was already rich and she was already at least in the background of the public eye because she was on Paris’ squad to begin with. To sum it up: Paris was popular, and becoming her suddenly seemed REAL and accessible for millions of girls who followed her and could buy stuff and dress like her and maybe could be popular (like her) too. Except it wasn’t true; it was all an illusion.

The Influencer Illusion

Back to Instagram. Like Paris and Kim, for nothing to really showcase other than being fabulous, Influencers sell popularity. And with an insatiable craving for ‘likes’ and ‘follows,’ new businesses developed to manufacture social media popularity: to “help” influencers (and everyone!) grow their following fast – if artificially.

Influencer Groups

First came the Influencer Groups: “influencers” gathered into groups and agreed on certain days and times when they would all upload new posts. At an agreed hour, they uploaded their posts and liked and commented on the posts of their fellow group members in a frenzy of contrived social media activity. Comments had to be at least one sentence long. This tricked both Instagram’s algorithm and advertisers into believing that these people are “influencers” because comments where usually something like “OMG gotta have this necklace,” or “I love your outfit, where did you get it?” which led advertisers to believe that these people really influenced, when in fact, there was no intention from group-mates to actually buy anything. The results were that these people APPEARED to be “influencers” when in fact it was all fabricated.

Followers for Sale

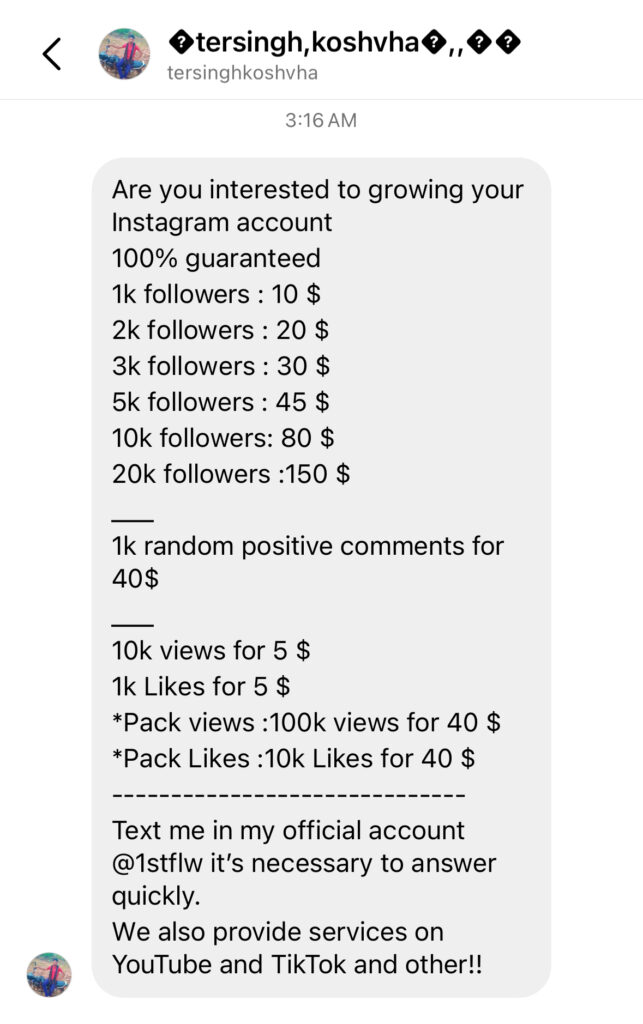

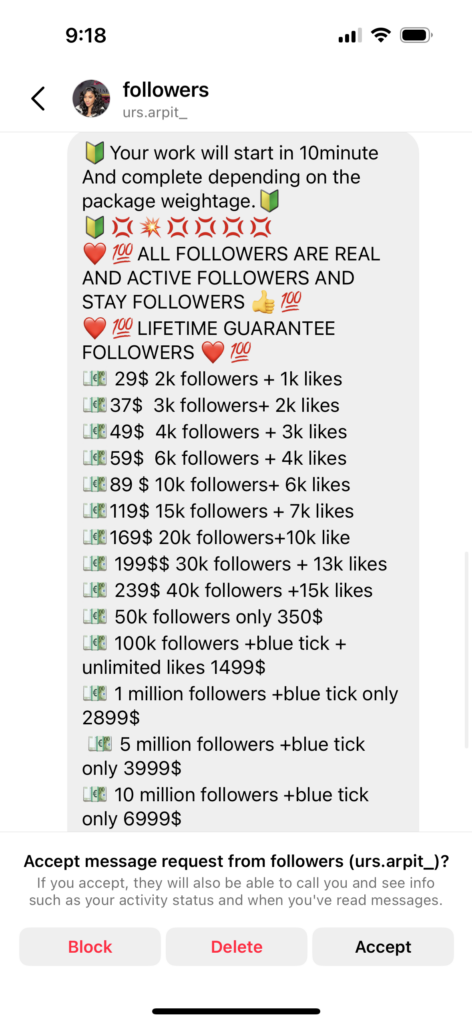

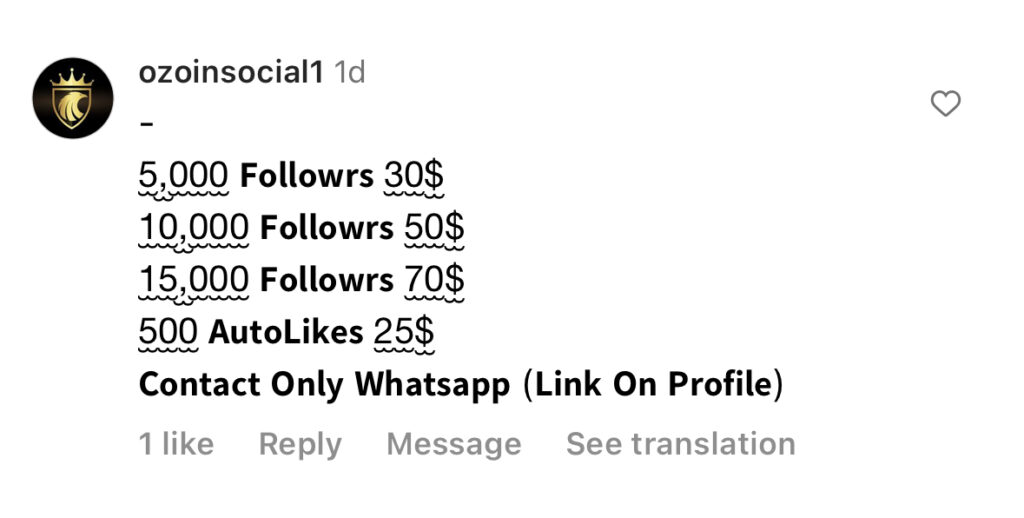

Then, the rise of “followers for sale.” Now anyone could have influencer numbers within a day. New companies sprung up that created thousands of profiles that were not actual people, offered them in private messages to people who were identified as “influencer wannabes” at an affordable price. Here are some examples (and rates):

Other companies, who aimed to help people get more followers, rode on the tendency for people to “follow back” people who followed them. They developed robots that follow active users and unfollow them a few days later. The result was a rapid growth of tricked “fans.”

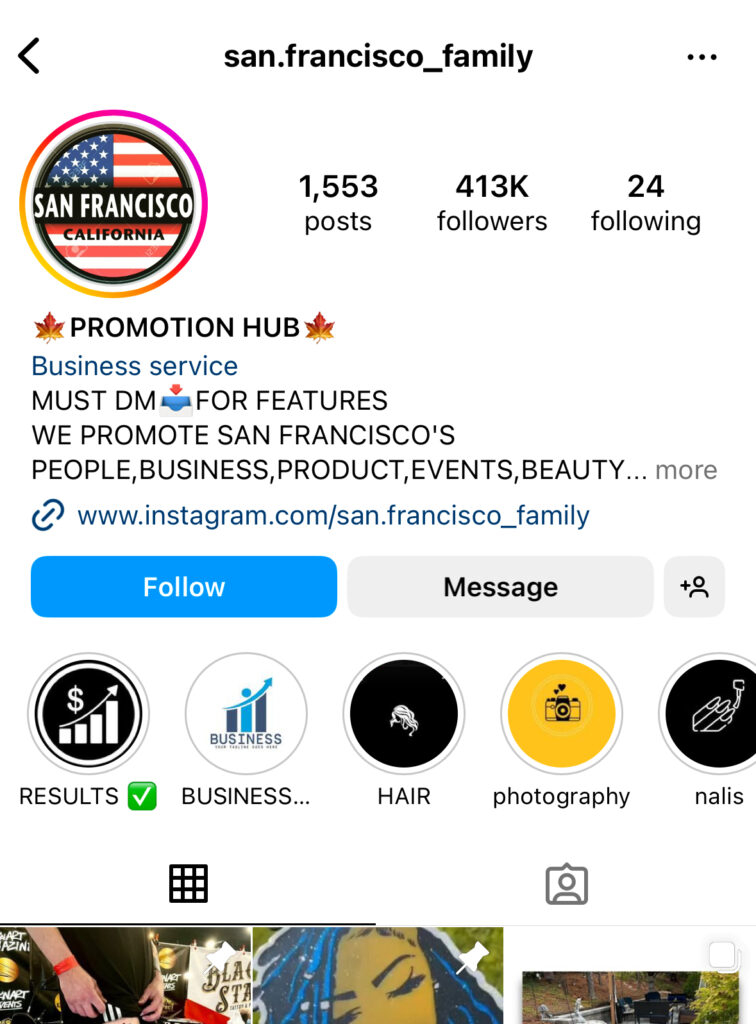

Another business model is one where profiles that seem to have thousands of followers comment on picture. “Send it to us,” they write. When the target sends it to them, they offer to give special exposure on their account for a price. Here’s an example:

These businesses made popularity available for everyone and it was hard to identify who was really an influencer. In the meantime, consumers’ attention spans continued getting shorter and shorter and advertisers began to understand that they were paying for ads that go by as quickly as peoples’ average scroll speed (which is less than one second). Also, we know that Instagram’s algorithm is designed in a way that a very small percentage of the followers see posts, and followers who liked or comment on previous posts are more likely to see them.

So the question remains: are “influencer posts” really influence? Do they really sell?

In my years working with both commercial and non-profit clients, I paid a small number of influencers for “collab” posts. No conversion was ever made in these experiences, meaning, none of the posts led to an actual sale.

What I learned from my short “Instagram influencer” days, is that there’s a pretty low bar for what you can ask your followers to do. They may like looking at you, but taking action – or certainly spending money is way beyond the line. And I think this is true not only for small-scale influencers.

Even Kim Kardashian Failed

In 2019, Israeli sunglasses brand Carolina Lemke paid Kim Kardashian $6 million to share their line of sunglasses on her social media. The company sought to expand into the American market and partnering with a mega influencer like Kim seemed like the right thing to do. But Kim’s attempt to push her followers to buy the glasses (rebranded “Carolina Lemke x Kim Kardashian”) failed. The company made a total profit of $1 million and had to collect 300,000 pairs of glasses back to its Tel Aviv warehouse.

While it’s really hard for influencers – big or small – to make people take actions, it’s pretty obvious that the ultimate influencer in this business is Mark Zuckerberg. He makes us all do and behave the way he wants us to. We are “rewarded” with the dopamine rush of people “liking” us when we post pretty pictures of ourselves. When he tells us to. We make stupid dance routine reels when he tells us to. We are creating content for him so that he can make more money from the ads he puts next to what we’re posting.

It Can Still Work (and with less mental health damage)!

Despite everything, it seems like “influencer” advertising isn’t going anywhere soon. I would like to offer my two cents on how it can work better, but it includes preaching about responsibility for the mental health of everyone (and maybe for the greater good of humanity):

It all comes down to creating meaningful content.

In all of my engagements supporting businesses and nonprofits on social media, and also in my own account, I always ask myself: what value is this account bringing to its followers? In the chaos of Instagram users’ facade of perfection which drives people to feel bad about their appearance, feel bad about what thery’re missing, and feel that they are not good enough – what am I giving them to lift them up, provide meaning, value. Give them a break from this madness? Oh – and, it turns out, creating meaningful, valuable content and personal connections with your followers actually helps SELL to them. Go figure!

Developing a talent or giving a service to your followers not only connects you with real followers, it can also be the source of meaningful content that shifts the focus away from perfectionism. If you want to make a real impact on social media, think about deeper connections with people, think about closing the gap between your “iInstagram life” and your actual life, and most of all – think about how you can help people to feel better or grow.

For advertisers, I always say it depends on who you are. If you are a small business or start-up company, targeted advertising on social media will do the work better for you for the same amount of money you pay for one influencer post. Remember that the scroll speed is often less than one second, and on top of that, each post is rarely shown for more than 10% of the account’s followers. Leave the influencer advertising to known brands, for which the influencer post is equivalent to a full page ad in a magazine in the dentist’s waiting room.

And to the question of who are the real influencers? My conclusion is that apart from celebrities who can speak to their devoted (rabid?) fans, the real influencers are you, me, and everyone. We are all influencers, we always have been. It’s that cute top that you see at the gym and want one too, it’s your friend’s story about a vacation in Whichita that makes you want to go, it’s a friend’s participation in a volunteering event that looks fun, feels meaningful. But somehow, it only works if the connection is real.